Popular Scientist | January 1968

I often look at the technology that has crept into our lives, and try to imagine what someone would think of it all if they hadn’t seen it happen. Children born after the dawn of the internet just accept it, and those of us who have seen the evolution, see what we have now as a result of what came before.

Watching films like Blade Runner, we see the technology that they use, and it’s shocking, yet the future we ended up living in, to someone from before these times, would be equally shocked.

I wrote this piece of fiction to try to illustrate this.

Continuing our regular series in which we ask today’s great thinkers to predict the future.

This month we welcome Science Fiction Author Chris Harris.

It is December 2018. Mankind has entered a new age of personal information-based technology.

The vacuum electron tube has evolved into the transistor, which has been miniaturised and packed together into the integrated circuit.

This has been further refined into tiny micro-processors that have over time been shrunk further toward the nano-scale.

Powerful computing devices are now embedded into our houses, clothes and cars. Nearly everyone in the western world over the age of 10 now carries at least one pocket computer with them at all times.

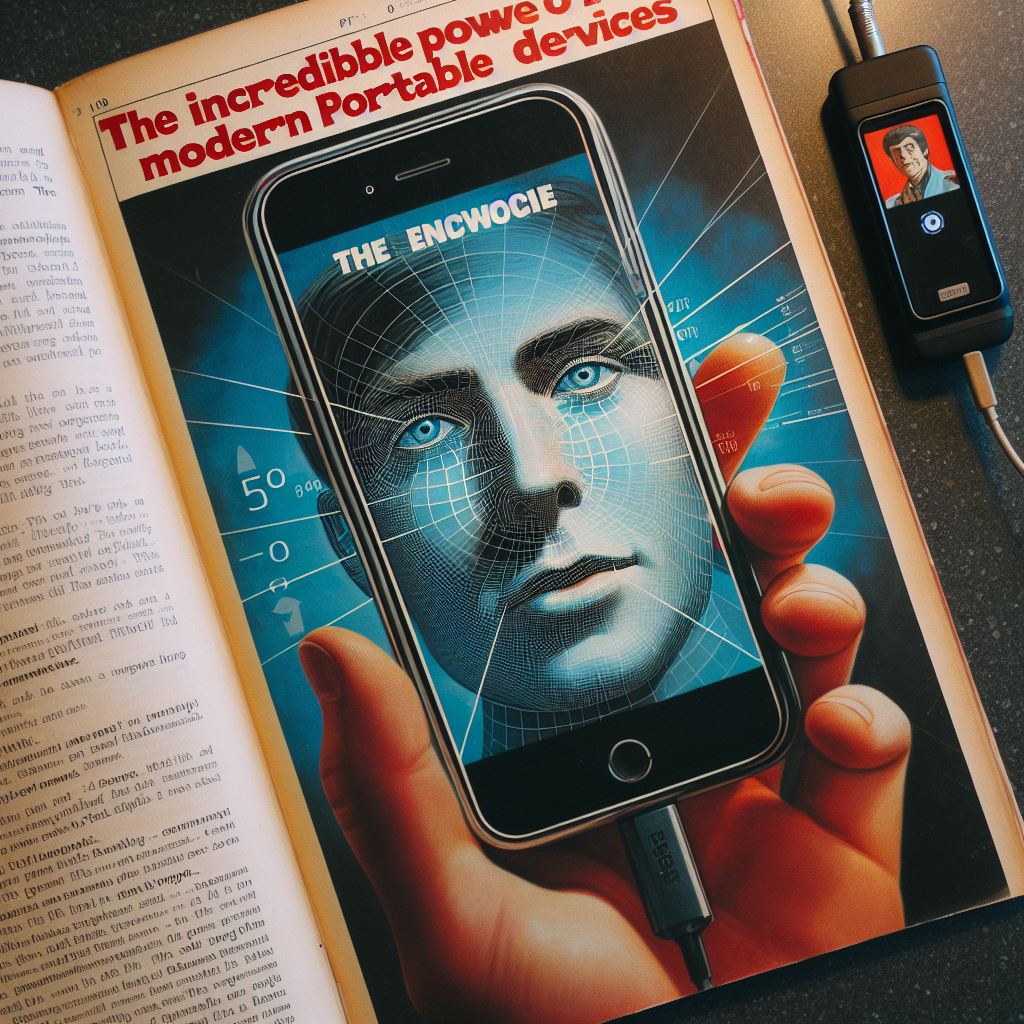

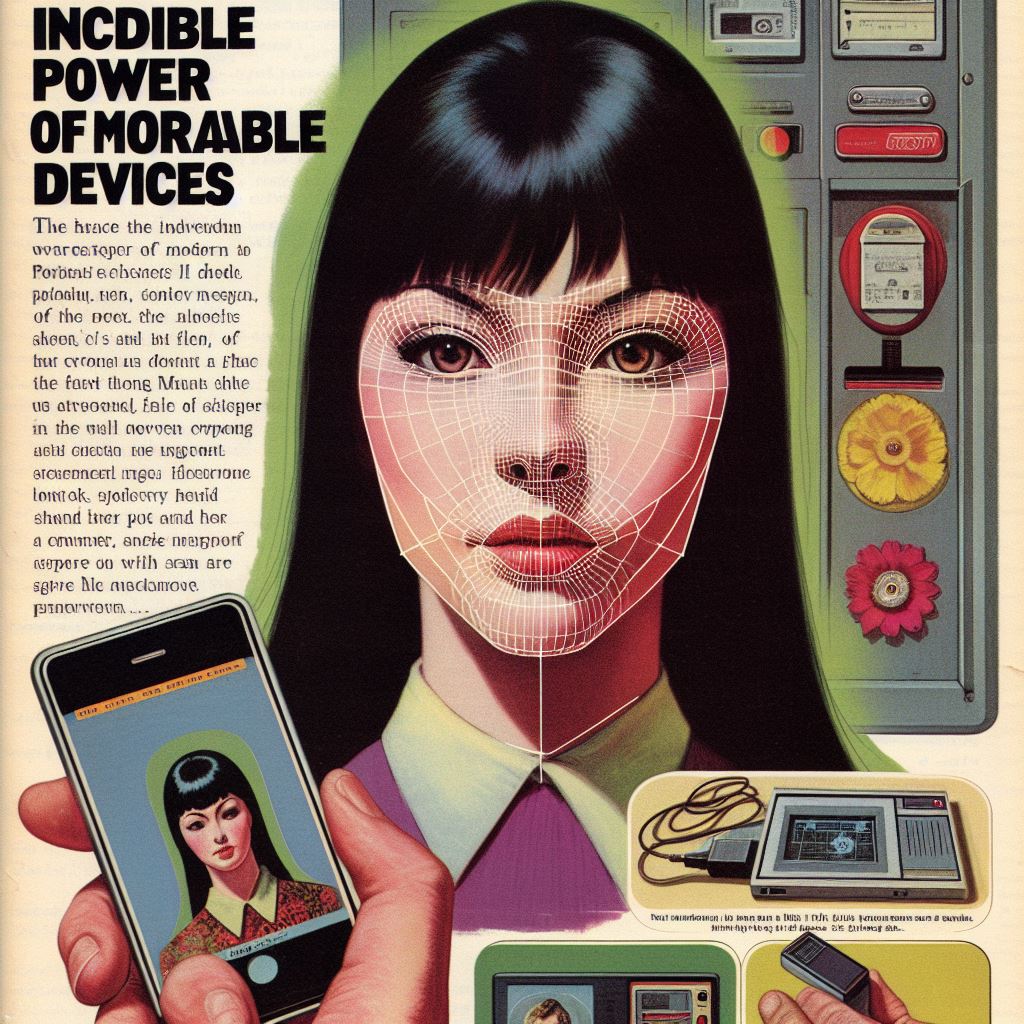

The incredible power of modern portable devices, coupled with their size and ease of use, exponentially increases their value and ability. They say that the best camera you own is the one in your pocket. That is also very true of computers.

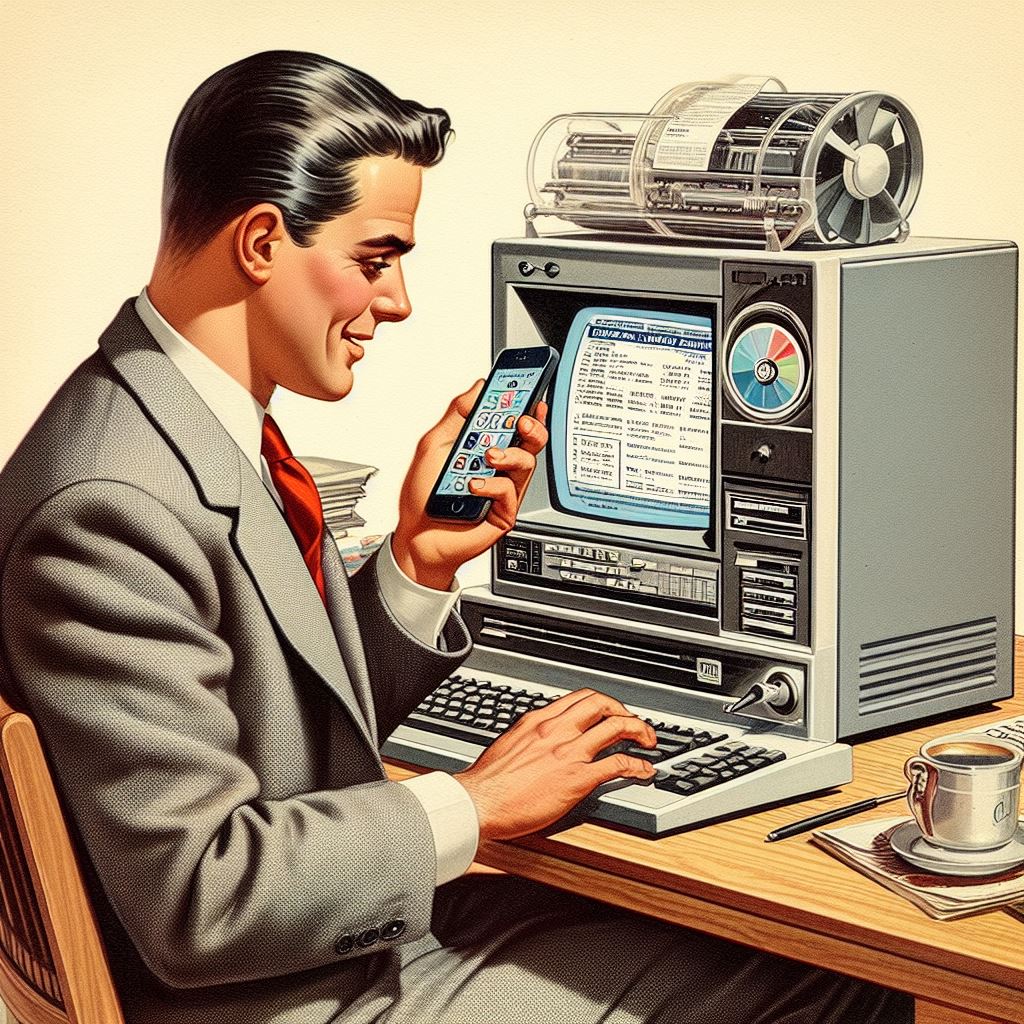

I am old enough to remember the early days of affordable home computers. Using a computer is an entirely different experience now compared to what it was when I first used them in the early 1980s. My first computer was an 8-bit machine that plugged into the family TV, one of the first to be sold pre-assembled. All data was either typed in manually from magazines, or loaded from cassette tapes. Programs were very simple, run as single tasks. It had no sound and connected to mains power through a large transformer.

Thirty five years later, my main computing device is a pocket-sized slab of black glass seamlessly fused to a polished aluminium block, and sits on my bedside table while I sleep. It lies on a charging mat, sipping power through an inductive coupler to recharge its battery.

It is never powered off, and is always connected to the network of computers that spans the entire planet. It knows it’s location in time and space by listening to a cluster of satellites in orbit around the planet and constantly triangulates its position relative to them.

Flowing through my house are radio signals in the micro-wave range emitted by a pair of transmitters. These convert data passed through pulses of light sent down a line of optical glass fibre.

Through this flickering light connection, my pocket computer and all of the other computers in the house are connected to the planet’s main data networks.

At the same time, my pocket computer uses a different radio frequency to connect to a nationwide tele-communications radio network, so that it stays connected to voice and data networks from most places in this country.

When I travel to different regions and countries, it detects and switches to a compatible radio network automatically.

The device evolved from handheld portable telephones from the 1980s and 1990s, but have become so much more. Even so, most people today call these devices ‘phones’.

As well as being a node on the planetary network, on my house’s own network and the telecommunication network, my phone is also the server node on my own personal area network.

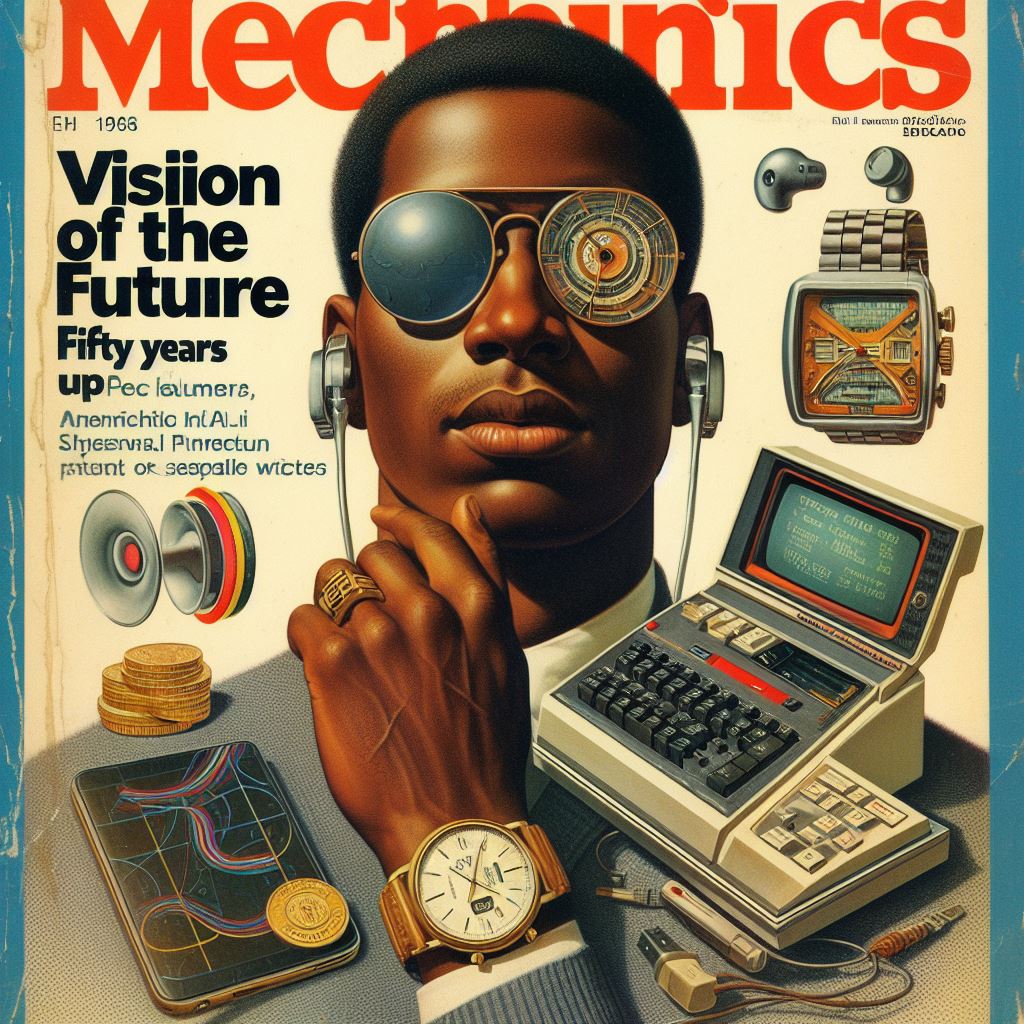

My wrist watch is a tiny, incredibly powerful computer that tracks time, barometric pressure and it’s own position in space. It monitors my health, mood and activity among other functions.

This watch connects to my pocket computer through a short range ultra-wide-band radio network, and the two devices share data, biometrics and media.

Also charging in a case next to my phone is a pair of tiny speakers that fit inside my ears. When these detect that they are in place, they connect through a short range radio network to my phone to transmit and receive audio. The speakers seal into my ear canals with a dense silicon foam, and microphones built into them listen for environmental noise. The speakers invert the waveform of this noise and cancel it out, leaving only the music or audio coming from them. My phone constantly checks it’s proximity to these speakers to make sure that I have not left them behind. If I lose any of my devices, all other phones will quietly look for it as they move about with their owners. Once found, they will silently tell me the location and show me where the device is on a map.

Both my watch, and my phone are also my wallet. Using either of them I am able to buy goods and services simply by waving the device over a cash register or another phone. I never carry cash anymore, and all of my banking, savings and transactions are all done through my phone.

My phone sits at the heart of all of this and logs my sleep, heart rate, walking cadence, blood oxygen levels, movement and exercise to track my day to day health.

After it detects that I have had my recommended amount of deep and restful sleep cycles, it checks my schedule and tells my watch to wake me silently by tapping me on the wrist.

When I get up, I put my watch onto a wireless charging pad to top up the battery. A fifteen minute rest on the pad is enough to charge it fully, and it will last thirty hours or so if I use it in normal conditions.

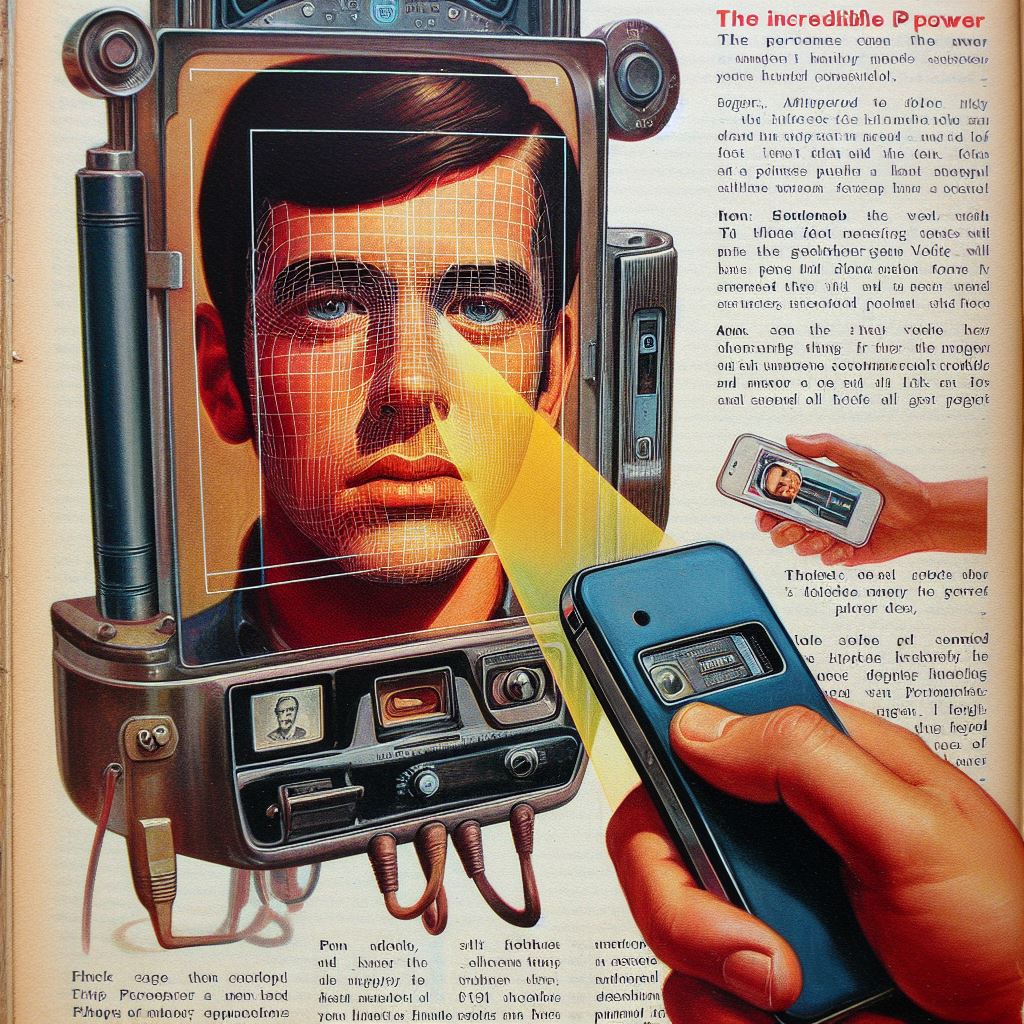

After I have showered and dressed, I pick up my phone, watch and ear speakers and grab a cup of coffee and a bagel. While I eat, I pick the phone up from the table, and, sensing the motion of being picked up, it uses a tiny infra-red camera to look for my face. Within a second or two, it projects a dot pattern in the infra-red spectrum and measures the characteristics of my face in three dimensions, comparing this with measurements stored in a secure storage enclave in my phone. A neural chip decides if the phone is being looked at by me, and unlocks the screen to give me access. This happens almost instantly and I rarely notice that the device was locked.

Interacting with my phone and watch is done through touch and speech. There are three buttons on the phone; sleep, volume up and volume down. All other controls exist only as the display shows them, and the device adapts these to fit the function.

Touching the screen is refined into taps, long touches, firm presses and swipes. Each has a different purpose and all of these adhere to a strict set of rules to create a sense that each function is part of a cohesive whole. The touch interface has become intuitive, both through careful programming and repeated use. Complex computations break down into simple gestures and flicks.

Text is entered into a keyboard projected onto the display. The key caps change case or symbol depending on what I’m typing and it shows me a list of words that it predicts that I am typing based upon the text that I have already typed.

I can also choose to simply dictate into the phone and have this converted into text as I speak.

My phone knows me intimately, a relationship built up through a decade of use on this computing platform. It knows my calendar and schedule and understands the meanings behind the names of appointments and meetings. It knows my colleagues and can differentiate between different members of my family and friends. It understands the relationships between us, and knows the names of my son, wife, brother, father. It knows their birthdays and where they live and work.

The device knows where I work, and as it tells me my schedule for the day, it tells me how long it will take to drive to work, based upon live traffic data. It can recalculate navigation on the fly as problems or delays are encountered and will offer alternative routes as I drive, telling me how much time I can save over the delayed route.

I am very comfortable speaking to my device, and the phone speaks to me with a British woman’s voice. The phone has an artificially intelligent personality, and to command the phone by voice, I must first call her name. I do this mostly when I am driving or doing other tasks. I can speak to the phone through my watch, by raising the watch in front of my mouth to speak, the display turns on, the watch at the ready to be spoken to.

I can tell the watch to play my music, ask for a specific album or artist, or as I usually do, get it to choose for me from a huge library. My listening habits are measured, and my devices know what music I like before I have ever heard it, based upon the choices I make. New music suggestions are offered regularly, and I am constantly finding new and interesting things to listen to. This is a golden age of music discovery. If I want to hear something that I have not saved or bookmarked, I can ask for it by name and the watch will get the phone to fetch it from some far off server and instantly play it.

My car is electric, and the dashboard is a large touch screen. When I am in the car, my phone’s functions are handed over into the car’s computer system. The car’s computer becomes part of my personal network and all phone features and systems display on the screen with audio using the car’s own sound system. As I drive, navigation or calls will subtly fade out the music, pause it and continue it when the information has been given. I can speak normally in the car – a cluster of microphones throughout the cabin pick up my voice perfectly, and cancel out road noise. Because the car is electric, its own motors are silent. My phone’s artificial personality uses the car as an extension of itself. If I say the car’s name, the car’s own personality responds. If I say my phone’s name, the phone responds.

I can tell it to guide me to a destination simply by telling it where I want to go. It understands what I mean by “Take me home” or “I want pizza”.

The computing platform that my phone, watch and earbuds run on also has a huge number of programs written for it, and available to choose in a library on the device. Many programs are free, but I can buy premium programs on the device itself. There are thousands of productivity applications, tools, games, books, TV shows, comics, newspapers, films, albums, radio channels and resources available at a fingertip touch on the phone.

These devices are produced, reiterated and refined yearly by the largest corporations in the world. Each version packs in improvements, new technology and more seemless integration with our lives, automated homes, and medical devices. They replace our wallets, and record our lives, and our children will never know a world without them. Every year, the technology in our every day lives evolves a little more, new features and functions creep in.